Build Your Own Static Vector Tile Pipeline

James GardnerFollowing on from James Milner’s introduction to Tiler, this post will drill into a little bit more detail about vector tiles, and the low-level commands tools like Tiler use behind the scenes. By understanding the commands, you’ll be able to build your own static vector tile pipeline.

NOTE: If you want to generate vector tiles that frequently need updating, you would be better off importing your data into PostGIS and then using a tool such as Tegola to generate them dynamically from the database as they are requested. The approach described in this post is better for generating a set of vector tiles all in one go.

This post describes the exact commands you’ll need to run assuming you are on the latest macOS (the most common set up amongst Engineers at the Hub at the moment). The same pipeline will work on Linux as well as previous versions of MacOS if you install the core tools we use yourself.

We’ll also assume you have a basic geospatial knowledge. If you haven’t, it is worth knowing that shapefiles, GeoJSON and TopoJSON are just ways of storing points, lines and areas. Within each file, each point, line or area is called a feature. Web maps generally load the data they need to display in tiles, small squares of data that each represent one small part of the map you are looking at.

Read this GIS File Formats page first for an overview of different approaches and their pros and cons.

It is also worth knowing that, slightly confusingly, a single shapefile is

actually distributed as four separate files, and that you need all four to be

able to work with the shapefile, not just the .shp file itself.

Throughout this tutorial we’ll be using compressed vector tiles that are smaller to store and quicker to transfer than their uncompressed counterparts.

Also, if you stop the tutorial and pick it up again, you’ll need to re-run all

the export commands to set up all your paths correctly again.

Mapbox Vector Tiles

Mapbox Vector Tiles are a modern way of storing and transmitting the same sort of feature data you might ordinarily find in a shapefile, GeoJSON or TopoJSON file.

There are two features of vector tiles that make them particularly interesting as a source format for displaying data on maps:

- In preparing the tiles, the data for the features the tileset represents is chopped up into individual tiles. This means the data for a large feature like a coastline will no longer exist as a single complex shape, but instead each tile that needs to display a portion of it will contain just the information needed to render the part of the coastline it is responsible for.

- Mapbox Vector Tiles are a compact binary encoding of the vector data called Google Protocol Buffers that is smaller than corresponding JSON, and usually smaller than a corresponding traditional raster tile too.

Because of these innovations, vector tiles have a major advantage over non-tiled formats like GeoJSON and TopoJSON:

- Map clients only need to download the data for the tiles they need to display, not all the data for all features that have some part on the map (as they would with GeoJSON or TopoJSON)

- Even if source GeoJSON or TopoJSON was prepared as separate tiles, Vector tiles can be obtained by browsers more quickly because they are a more compact binary format so file sizes are lower.

Being a vector format (containing portions of the actual source data), vector tiles have advantages over traditional raster tiles (just pictures of the pre-coloured data) too:

-

Map clients can access the vector data directly so have the ability to re-colour or style the data dynamically themselves without needing to load more data from the server (something that can’t be done with raster tiles, which are just images of the data)

-

Map clients can zoom in and out smoothly between the different zoom levels because the data can be easily scaled while new data is loaded. This is known as over-zooming or under-zooming.

-

Vector tiles often have smaller file sizes than raster tiles. For example imagine you want to draw a line. In an image, you’d need to colour in each pixel between the start and end point (perhaps 20 numbers), whereas as a vector, you just specify numbers for the start and end point.

These advantages of vector tiles all add up to:

- A faster and smoother experience for the end user

- Lower bandwidth costs for the hosting

- The potential for building more advanced map applications that make use of the data transmitted

Hosting

Vector tiles are also fairly easy to host cheaply since they can be represented as a simple directory structure of files.

Google Cloud Storage is one place to host the tiles so that they can be retrieved by a map client. The advantage over running your own server is that Google will look after keeping the files accessible so that you don’t need hosting expertise or 24 hour monitoring and response to keep your tiles available. It is also a cheaper option than hosting directly with Mapbox.

Modern browsers are able to read compressed files directly if they are compressed in gzip format and served with the following header:

Content-Encoding: gzip

In this post we’ll assume you have a host that is capable of adding this header to HTTP responses so that we can store and transfer compressed tiles, rather than uncompressed ones which take up more space and take longer to transfer.

Getting Started

To get started, why not download some shapefiles for London to experiment with from the Ordnance Survey Open Local download page.

You’ll need to tick the box to the right of the National Grid Reference

squares label, in the Download column, and then scroll down to select TQ

from the list next to the grid squares diagram. Scroll to the very bottom of

the page, click Continue and follow the instructions.

The page mentions that it can take up to 2 hours to fulfil the request. In practice it is nearly instant so don’t be put off.

Repeat the process to download the TR grid square data too. (You can also

request them both at the same time by selecting them both to start with).

Note: Each download has a data directory containing different shapefiles

representing the different types of data available. For example, the shapefile

for the roads in the TQ square actually comes as TQ_Road.shp,

TQ_Road.shp, TQ_Road.shp and TQ_Road.shp. Tiler will automatically

extract the data from the archives you’ve downloaded as long as you use the

correct name, in this case Road.

Next you must download the ostn02-ntv2-data.zip file from OS

here.

It contains the OSTN02_NTv2.gsb file you need in order to get the high

resolution transforms from British National Grid into WGS84 that we need.

At this point make a directory named src. Extract the ostn02-ntv2-data.zip archive and copy the

OSTN02_NTv2.gsb file into the src directory.

Finally put the two zip files you’ve downloaded for TQ and TR in the src

directory too, next to OSTN02_NTv2.gsb.

You should now have an src directory containing 3 files and nothing else:

OSTN02_NTv2.gsbopmplc_essh_tq.zipopmplc_essh_tr.zip

We’ll now write some re-usable commands to process this data, without any manual steps. This will then scale to more layers later.

Install the Tools

If you have Homebrew installed you can use the brew

command to install GDAL:

brew install gdal tippecanoe

If you already have them installed, upgrade to the latest versions:

brew update

brew upgrade gdal tippecanoe

Otherwise, follow the advanced instructions below.

Advanced Install

NOTE: You can skip this section if you used the brew option above.

Download and install GDAL by following the download instructions.

Next install the very latest version tippecanoe. To do this you’ll need the Xcode command line tools. They come automatically if you install Xcode, or if you have tried to use command line tools in the past. If you don’t already have Xcode command line tools installed, you can install them from a terminal.

To get a terminal, click the spotlight search icon in the bar at the top right of your screen (it looks like a magnifying glass) and type “Terminal”. Click the terminal icon.

At the terminal type cc and press enter and you’ll be prompted to install the

Xcode command line tools. Follow the instructions. If instead you see a clang

error, that means you already have the tools.

Next download the latest tippecanoe from here:

Double click it to unzip it to a tippecanoe-master folder

You can now install it by typing these commands at a terminal:

cd ~/Downloads/tippecanoe-master

make

export PATH=~/Downloads/tippecanoe-master:$PATH

You should now be able to run the following two commands:

ogr2ogr --version

tippecanoe -v

On my computer I get:

GDAL 2.1.2, released 2016/10/24

tippecanoe v1.18.1

You’ll need at least tippecanoe 1.18.1.

Extract the files from the downloads in src

First create a build directory for your work, next to the src directory

(not inside it).

Now run this command in the directory that contains your src and build

directories. It will extract the OS data into build/shapefiles:

find "src" | grep ".zip" | xargs -n1 unzip -d "build/shapefiles"

If you run it from the wrong place, it won’t be able to find the src

directory.

Find the Road shapefiles from each grid square

The OS road layer is named Road so we need to find all the road shapefiles

that we just extracted into /build/shapefiles.

We can find them like this:

export LAYER=Road

find "build/shapefiles" | grep "_${LAYER}.shp" > "build/${LAYER}_shapefiles.txt"

You can see the shapefiles we found with:

cat "build/${LAYER}_shapefiles.txt"

I get:

build/shapefiles/OS OpenMap Local (ESRI Shape File) TQ/data/TQ_Road.shp

build/shapefiles/OS OpenMap Local (ESRI Shape File) TR/data/TR_Road.shp

Merge the Road shapefiles togehter

Now we need to put all the shapefiles together. Slightly confusingly the

ogr2ogr tool from GDAL requires us to do this in two commands (it is just the

way it works).

The first command will take the first shapefile and makes a copy of it. The second command is used for appending the other shapefiles to the first.

Let’s set the layer we want again:

export LAYER=Road

Now here’s the first command for copying the first shapefile:

ogr2ogr -f 'ESRI Shapefile' "build/$LAYER.shp" -nln "${LAYER}" "`cat "build/${LAYER}_shapefiles.txt" | head -n 1`"

You can now see the four files that make up the Road shapefile in build.

Now let’s append all the other shapefiles (in this case there is only one,

TQ, but there might be more later:

cat "build/${LAYER}_shapefiles.txt" | tail -n +2 | while read line; do

ogr2ogr -f 'ESRI Shapefile' -update -append "build/$LAYER.shp" "$line" -nln "${LAYER}"

done

Generate a GeoJSON file

tippecanoe which will eventually generate out vector tiles requires a GeoJSON

file as input, so we need to convert the Road shapefile to GeoJSON.

One complication is that our source data is in a British National Grid projection but we need it in WGS84 (a.k.a EPSG:4326) for GeoJSON, so as well as converting formats, we’ll re-project the data too.

We can do this all in one step like this, using the OSTN02_NTv2.gsb file you

put in the src directory earlier:

mkdir build/geojson

export LAYER=Road

ogr2ogr -dim 2 -f 'GeoJSON' -s_srs "+proj=tmerc +lat_0=49 +lon_0=-2 +k=0.999601 +x_0=400000 +y_0=-100000 +ellps=airy +units=m +no_defs +nadgrids=./src/OSTN02_NTv2.gsb" -t_srs 'EPSG:4326' "build/geojson/$LAYER.json" "build/$LAYER.shp"

This is a little complex, because it is reprojecting data as well as changing its format, but you can look at these links to understand it:

- Why transforming data in the UK is so important for GIS

- OSTN02 – NTv2 format

- Transformations to OSGB36 and WGS84 in GDAL/OGR

- GDAL info about a number of SRS sources

- A guide to coordinate systems in Great Britain PDF

Now we have the Road.json file in build/geojson.

Run tippecanoe to generate a directory of Mapbox Vector Tiles

We can finally generate compressed vector tiles with this command for hosting:

tippecanoe --no-feature-limit --no-tile-size-limit --exclude-all --minimum-zoom=5 --maximum-zoom=g --output-to-directory "build/www/tiles" `find ./build/geojson -type f | grep .json`

By default, tippecanoe will create one Vector Tile layer per .json file,

and name it according to the JSON filename. In this case with just one .json

file, it will create a set of tiles with just one layer named Road. Rename

the file before running the command if you would like it named differently.

There are lots of options you can use, but our experience has been that the

automatic simplification options such as --drop-fraction-as-needed don’t

produce good results. Simplifying isn’t easy, and it becomes partly an issue

of cartography.

Just to describe two of the options chosen in particular:

-

--minimum-zoom=5- Don’t generate tiles for layers below 5, there will be too much data for the clients to be able to display them smoothly anyway. -

--maximum-zoom=g- Lettippecanoeguess the maximum zoom level based on how close together the data is (makes sure we don’t generate more tiles than we need to) -

--exclude-all- Don’t include attributes about the features in the tiles, only include the vector data itself (keeps the tiles small)

It is likely that in future, you’ll want to use --include instead of

--exclude-all to keep specific attributes attached to the vector data (such

as road names for example) but for now we’ll strip all the extra data out to

keep the tiles small.

Have a look at the tippecanoe docs and feel free to experiment with different options.

ADVANCED TIP: Through a lot of trial and error I’ve found that if your tiles end up too big to display well in a particular client, it is much better to filter the data in the input files at the start of the process for different zoom levels, than to try to automatically simplify later.

Pipeline

Putting everything together, we now have this set of commands to perform

all the steps run so far to generate a new build directory when run in a

folder with the src directory:

export LAYER=Road

mkdir -p build/www/tiles/

find "src" | grep ".zip" | xargs -n1 unzip -d "build/shapefiles"

find "build/shapefiles" | grep "_${LAYER}.shp" > "build/${LAYER}_shapefiles.txt"

ogr2ogr -f 'ESRI Shapefile' "build/$LAYER.shp" -nln "${LAYER}" "`cat "build/${LAYER}_shapefiles.txt" | head -n 1`"

cat "build/${LAYER}_shapefiles.txt" | tail -n +2 | while read line; do

ogr2ogr -f 'ESRI Shapefile' -update -append "build/$LAYER.shp" "$line" -nln "${LAYER}"

done

mkdir build/geojson

ogr2ogr -dim 2 -f 'GeoJSON' -s_srs "+proj=tmerc +lat_0=49 +lon_0=-2 +k=0.999601 +x_0=400000 +y_0=-100000 +ellps=airy +units=m +no_defs +nadgrids=./src/OSTN02_NTv2.gsb" -t_srs 'EPSG:4326' "build/geojson/$LAYER.json" "build/$LAYER.shp"

tippecanoe --no-feature-limit --no-tile-size-limit --exclude-all --minimum-zoom=5 --maximum-zoom=g --output-to-directory "build/www/tiles" `find ./build/geojson -type f | grep .json`

Generate a sample Mapbox GL JS web app

Now you’ve generated the tiles, let’s create a web map to have a look at them.

Add some files to the /build/www directory created by tippecanoe:

cat << EOF > "build/www/index.html"

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>Map</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="initial-scale=1,maximum-scale=1,user-scalable=no" />

<script src="https://api.mapbox.com/mapbox-gl-js/v0.35.1/mapbox-gl.js"></script>

<link href="https://api.mapbox.com/mapbox-gl-js/v0.35.1/mapbox-gl.css" rel="stylesheet" />

<style>

body { margin:0; padding:0; }

#map { position:absolute; top:0; bottom:0; width:100%; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div id="map"></div>

<script>

mapboxgl.accessToken = "not-needed-unless-using-mapbox-styles";

var map = new mapboxgl.Map({

container: "map",

style: "http://localhost:8000/style.json",

center: [-0.1047, 51.5236],

// These affect the hard limits of the zoom controls

minZoom: 5,

zoom: 11,

maxZoom: 22

});

map.addControl(new mapboxgl.NavigationControl());

</script>

</body>

</html>

EOF

cat << EOF > "build/www/style.json"

{

"version": 8,

"name": "Custom",

"metadata": {

"mapbox:autocomposite": true

},

"glyphs": "mapbox://fonts/mapbox/{fontstack}/{range}.pbf",

"sources": {

"composite": {

"type": "vector",

"tiles": ["http://localhost:8000/tiles/{z}/{x}/{y}.pbf"],

"minzoom": 0,

"maxzoom": 15

}

},

"layers": [

{

"id": "background",

"type": "background",

"paint": {

"background-color": "#e3decb"

}

},

{

"id": "Road",

"type": "line",

"source": "composite",

"source-layer": "Road",

"minzoom": 0,

"maxzoom": 22,

"paint": {

"line-color": "#FFFFFF",

"line-width": 0.5

}

}

]

}

EOF

Keeping the styles all in an external style.json is a bit different from the

examples you’ll see online for Mapbox GL JS, but the advantage is that the same

style formats will work with the other clients such as Mapbox GL iOS and Mapbox

GL Android.

Under and Overzooming

One of the nice features of vector tiles is that you don’t necessarily need to generate tiles for every zoom layer the browser supports. As long as you tell Mapbox which tiles exist in each source, it can use the vector data to dynamically resize the information from the closest tiles that are available. This is known as under- or over-zooming.

The minzoom and maxzoom settings in the composite source specify which

zoom levels the source physically contains files for (which zoom levels you

generated with tippecanoe).

The minzoom and maxzoom in each style layer can be different from the

values specified in the source (as long as they are within the bounds specified

by maxZoom and minZoom (note the capital Z) in index.html. If they

extend beyond the values you have tiles for, the Mapbox tile client will

over-zoom or under-zoom based on the nearest available tile.

In this case, it means roads will still be visible in the map at zoom level 22, even though we only have tiles for level 15.

Since we’re only using up to zoom level 5, we didn’t technically need to generate tiles 0-5.

Local Server

Now you can run a server capable of correctly serving gzipped vector tiles by

adding a Content-Encoding: gzip header to each response. (The added header

means the browser will unzip the tiles before passing them to the Mapbox

client, so that Mapbox still gets the unzipped tiles, but you only need to

transmit and store compressed ones).

One suitable server is live-server running with a middleware plugin, but it is a bit fiddly to set up.

To use it you’ll need to install Node Current, for example with this command:

brew install node@7

Then install live-server like this:

npm install live-server

This will create a node_modules/.bin directory containing live-server. Add this to your path:

export PATH=$PWD/node_modules/.bin:$PATH

You can create support for gzipped tiles by creating this file:

cat << EOF > "build/gzip.js"

module.exports = function(req, res, next) {

if (req.url.endsWith('.pbf')) {

next();

res.setHeader('Content-Encoding', 'gzip');

} else {

next();

}

}

EOF

Then run the server like this:

live-server --port=8000 --middleware="${PWD}/build/gzip.js" --host=localhost build/www

There you go, your very own Vector Tiles!

Styling for Different Zoom Levels

If you play with the example as it stands, you’ll notice that things get pretty crowded as you zoom out. You might want to change the road thickness to become thinner as you zoom out.

Try replacing the single road style layer you have so far in

build/www/style.json with these three style layers, which change the width

depending on the zoom range:

{

"id": "Road",

"type": "line",

"source": "composite",

"source-layer": "Road",

"minzoom": 13,

"maxzoom": 15,

"paint": {

"line-color": "#FFFFFF",

"line-width": 3.5

}

},

{

"id": "Road2",

"type": "line",

"source": "composite",

"source-layer": "Road",

"minzoom": 10,

"maxzoom": 13,

"paint": {

"line-color": "#ffffff",

"line-width": 1.5

}

},

{

"id": "Road3",

"type": "line",

"source": "composite",

"source-layer": "Road",

"minzoom": 0,

"maxzoom": 10,

"paint": {

"line-color": "#ffffff",

"line-width": 0.5

}

}

CAUTION:

-

When you are changing the styling, make sure you put the background layer first, otherwise you’ll paint a background over the top of everything and see nothing!

-

Make sure you give each layer a different

id, even if it is actually using the same source and layer in the underlying vector tiles otherwise Mapbox won’t be able to render it correctly.

When you’ve finished styling the map, live-server should automatically reload

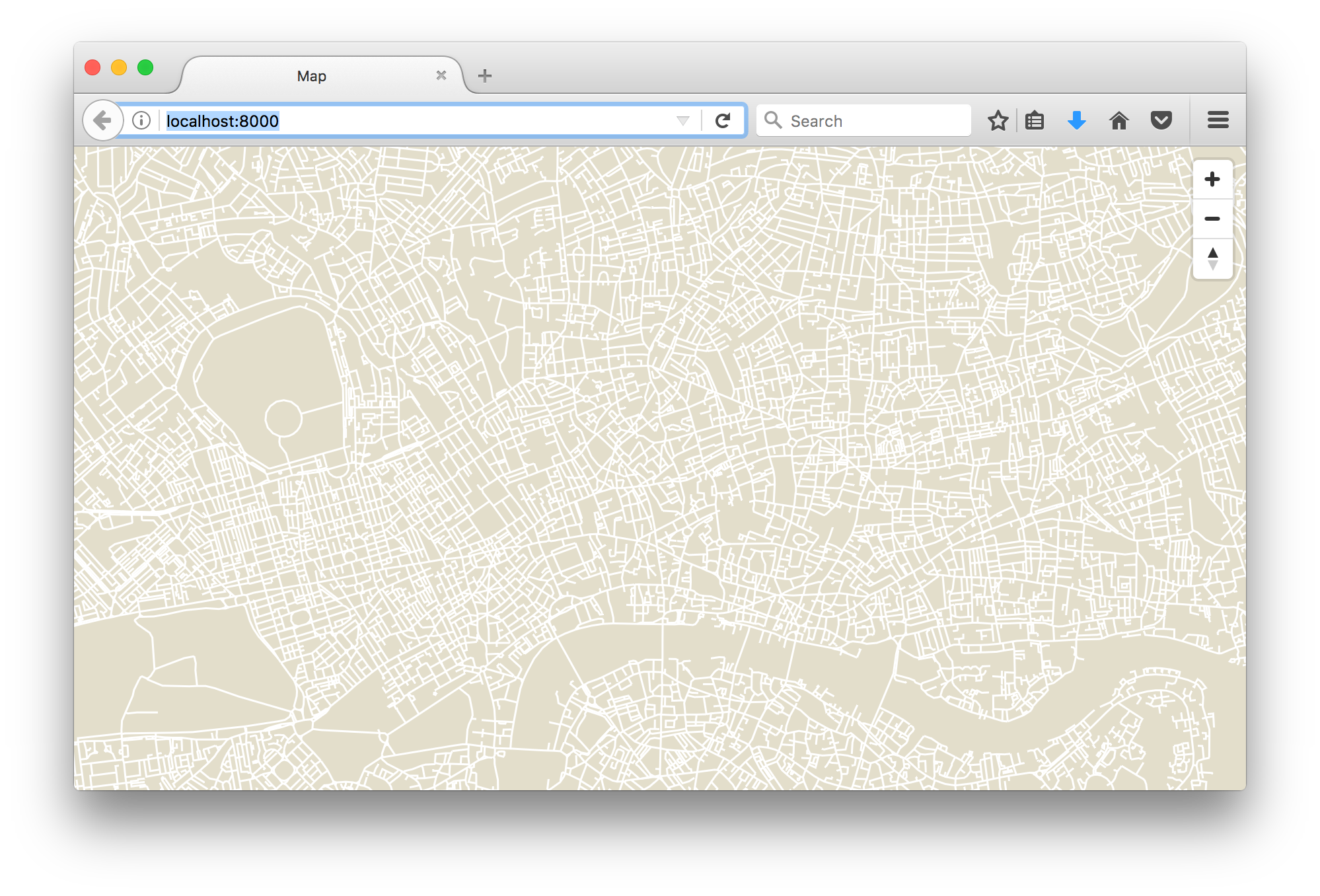

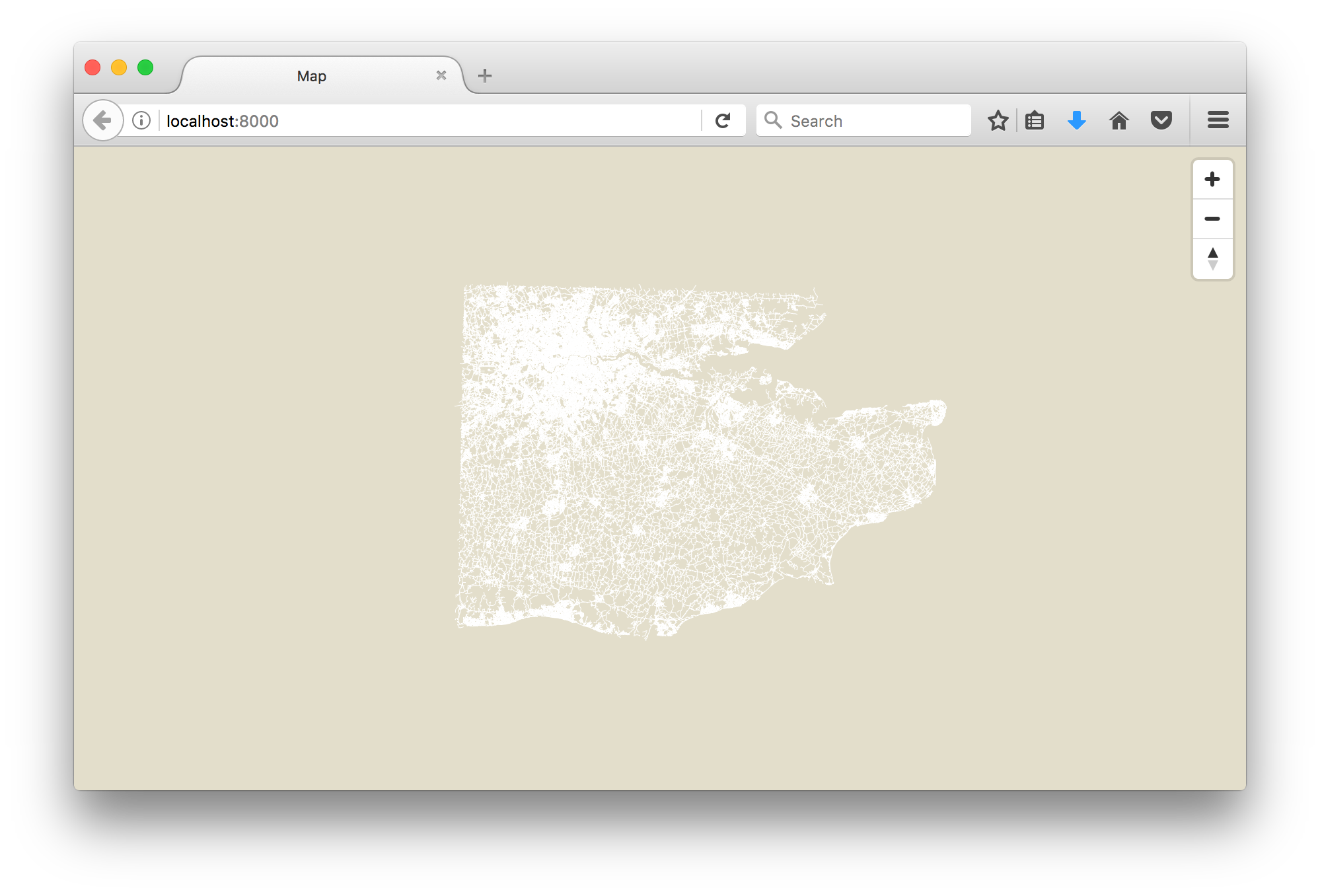

and you’ll get his map:

If you zoom out a bit you’ll see the extent of the data you’ve generated tiles for. Notice that all the roads are shown, but the individual road widths is thinner because of the styles you’ve set for each zoom range.

These screenshots contain OS Open Local data © Crown copyright and database right 2017

Advanced Styling Based on Attributes

Whilst changing styling based on zoom level is handy, it is also useful to be able to style the one vector tile layer in different ways according to the data it contains. In the case of roads, you might want main roads like A roads and motorways to be styled differently from B roads. You might want minor roads to only be visible when you are quite zoomed in.

You can achieve this with attributes and layer style filters.

When you ran tippecanoe you used the --exclude-all option to exclude all

the attribute data from the original shapefiles. This time, let’s use

--include to include just one attribute of the Road shapefile called

CLASSIFICA:

mv build/www/tiles build/www/tiles.old

time tippecanoe --no-feature-limit --no-tile-size-limit --include="CLASSIFICA" --maximum-zoom=16 --output-to-directory "build/www/tiles" `find ./build/geojson -type f | grep .json`

The tiles generated this time will include this extra data.

There is plenty of documntation on the OS Open Local data and in particular, the Product Guide pag 14 describes the Road attribute classifications:

- A Road

- B Road

- Local Road

- Local Access Road

- Restricted Local Access Road

- Minor Road

- Primary Road

- Motorway

- A Road, Collapsed Dual Carriageway

- B Road, Collapsed Dual Carriageway

- Minor, Collapsed Dual Carriageway

- Primary, Collapsed Dual Carriageway

- Motorway, Collapsed Dual Carriageway

- Shared use Carriageway

- Guided Busway Carriageway

ADVANCED TIP: There is a program called QGIS that you can install that helps

you work with shapefiles. If you drag the TQ_Roads.shp file into QGIS it will

draw all the roads for you. If you click the Open Attribute Table button

you’ll see a table of all the attribute data available, and the names of the

columns.

This means that now in the style layers, you can choose which features get styled by filtering only the features that have the attributes you want to style.

Here’s an example where we create three road style layers, each with a

different filter that uses the CLASSIFICA attribute. Note that some of the

style laters only show at certain zoom levels.

{

"id": "Road",

"type": "line",

"source": "composite",

"source-layer": "Road",

"minzoom": 12,

"maxzoom": 15,

"paint": {

"line-color": "#FFFFFF",

"line-width": 1.5

},

"filter": ["!in", "CLASSIFICA", "A Road", "A Road, Collapsed Dual Carriageway", "Motorway", "Primary Road", "Primary Road, Collapsed Dual Carriageway", "B Road"]

},

{

"id": "MajorRoad",

"type": "line",

"source": "composite",

"source-layer": "Road",

"minzoom": 0,

"maxzoom": 15,

"paint": {

"line-color": "#000000",

"line-width": 3.5

},

"filter": ["in", "CLASSIFICA", "A Road", "A Road, Collapsed Dual Carriageway", "Motorway", "Primary Road", "Primary Road, Collapsed Dual Carriageway"]

},

{

"id": "BRoad",

"type": "line",

"source": "composite",

"source-layer": "Road",

"minzoom": 0,

"maxzoom": 15,

"paint": {

"line-color": "#888",

"line-width": 1.8

},

"filter": ["in", "CLASSIFICA", "B Road", "B Road, Collapsed Dual Carriageway"]

}

Summary

At this point you’ve successfully build a map using Vector Tiles that has different layers (roads and tidal water), and has different style layers for the road layer.

This is a great achievement! There’s still a lot more to learn about vector tiles including sprites, labels and simplification, but hopefully getting this far will have given you a great starting point for your explorations.

Feel free to leave questions or comments below and I’ll try my best to answer them.

Creative Commons Share-a-like James Gardner © Geovation

Leave a Comment